Announcements

Drinks

US trade policy: wide-ranging tariff increases heighten global credit risk

By Dennis Shen – Scope Macroeconomic Council

The balance of risks for the global and European economies remains negative. This considers four inter-related dynamics: i) trade tensions and the acceleration of de-globalisation; ii) elevated risk for financial markets and financial stability; iii) government budgetary challenges and associated more regular re-appraisals of sovereign debt risk; and iv) geopolitical concerns. Together, these factors represent a core challenge for the global credit outlook.

The tariff measures introduced by President Donald Trump have been more significant in size and breadth than anticipated. The roll-out of the new trade policy has also been faster – taking place well inside his first 100 days in office – than the more gradual approach adopted during his first term.

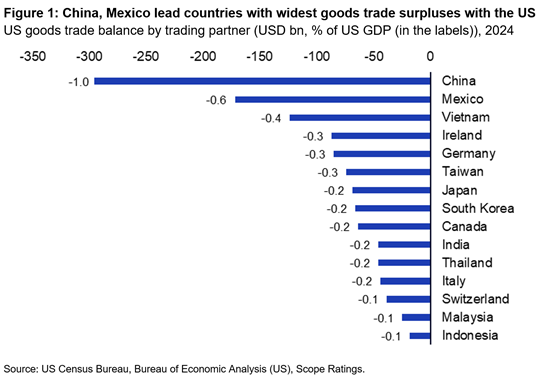

The 10% US tariffs imposed on most trading partners came into effect last weekend, although the additional customised tariffs of up to 50% on around 60 countries have been delayed 90 days except for those on China. The paused “reciprocal” tariffs have been based on a formula using the size of the US’s goods trade deficits in 2024 with its trading partners (Figure 1).

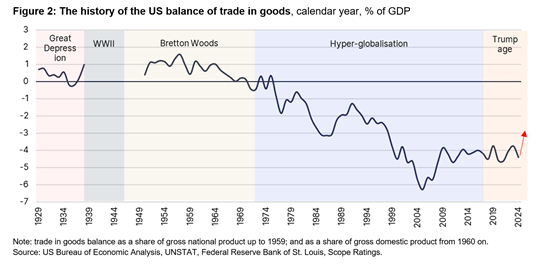

Even after the pausing of some of the biggest of “Liberation Day” tariffs, the effective tariffs nonetheless mark the highest US import tax burden in a century, reversing decades of multi-lateral and bilateral trading agreements adopted under the US-driven globalisation after the Second World War.

The “Trump Put” appears again

Among the conventional checks on the Trump presidency has been the effect of his tariff-related policies on the broader economy and financial markets. The so-called “Trump Put” – the assumption that policy making moderates in response to market declines – re-appeared this week after stock and bond markets declined, even though Trump’s tolerance for economic and financial-market fall-out has proven to be greater than that during his first presidency. Trump has described his tariffs as the “medicine” necessary to correct outstanding trade imbalances, having earlier suggested that rates may be reduced from the announced ceilings only if trade deficits narrow first.

Uncertainty surrounds the future of the trade war

The US trade deficit may well be reduced from the current highs (Figure 2), but this is unlikely to be driven by a near-term structural re-orientation in trade but rather because of the sharp downturn in the domestic economy, moving from a state of over-heating entering 2025 to facing recession.

Pressure has been building on the administration from scepticism among segments of the electorate on the handling of the economy, as price rises accelerate rather than ease. Furthermore, 54% of families have market-based retirement plans, vulnerable to the volatility in stock markets. Inside Congress, there are Republican Party efforts at re-asserting Congressional control over tariff policies as the party confronts risks for the economy alongside concerns about the political consequences for the 2026 mid-term elections.

For the moment, the US president is both intensifying trade war with China, increasing tariffs to 125%, while offering a degree of temporary reprieve for other trading partners. Given the structural nature of bilateral trade imbalances, with many low-wage emerging markets that are core suppliers of affordable imports, the US tariffs on these countries may remain higher in some form for longer.

The impact on the US economy has been severe

The economic consequences of the current trade policy stance are proving severe for the US economy. Trump inherited an economy demonstrating significant resilience after the most rapid rise in official interest rates on modern record, such as above-potential growth of 2.8% last year, but the new trade policy has resulted in a sharp reversal in fortunes, with the risk of a technical or calendar-year recession – or both – this year.

Efforts at restoring domestic manufacturing and assembly-line jobs in the US while diminishing global trade fundamentally may weaken the economy in the longer run as new factory jobs require significant investment and many years to upscale. In addition, the advance of automation in industry is such that opening new factories creates far fewer manufacturing jobs than before.

Monetary divergence as certain central banks cut whereas stagflation constrains peers

As the global economic outlook weakens, many central banks may react with counter-cyclical rate reductions. However, even as central banks such as the European Central Bank may cut rates again nearer term, others such as the Federal Reserve may stay on hold. There are risks for the global economy in just how much the Federal Reserve and other central banks confronting stagflation can support the economy if present economic and financial instability increases.

This is because US trade policy has uneven effects on inflation, with uneven consequences for monetary policies. Higher inflation for American consumers contrasts with the near-term disinflationary force in countries that hold back from immediate counter-tariffs and benefit from discounted global goods re-routed from the US. In the medium run, initially temporary inflation from tariffs, counter-tariffs and supply-chain disruption might easily become more persistent.

The ripple effects for the global economy and Europe

Given the weight of the US economy, the possibility that Trump again escalates the trade war puts stress on the global economy at large.

The case of China is crucial. China – being the largest economy globally on purchasing-power-parity terms – has matched former 50% tariffs imposed by the US, after responding to the 54% tariffs beforehand with reciprocal 34% duties on American imports alongside restricting exports of crucial rare-earth minerals. This marked a break from China’s historically patient and less conflictual approach with Trump.

The tariff blow to the Chinese economy comes when it is already facing structural slowdown and deflation, requiring further government spending to counteract the effects of the trade war. This heightens pre-existing financial-stability risks for the Chinese economy.

The economy of the European Union is also vulnerable. The US is the largest single export market for EU-made goods, accounting for nearly 21% of EU exports last year. The EU has Thursday suspended its latest response to Trump’s trade war, which targeted around EUR 21bn of US goods including agricultural products and motorcycles with tariffs of up to 25%.

EU economies most exposed to the policy shifts are those displaying wide trade surpluses and significant trade with the US such as Germany and Ireland. If the EU does retaliate further against the US, this may present a greater conundrum for the ECB’s easing plans.

This is an updated version of a research commentary originally published on Wednesday, 9 April before the US government suspended some of its reciprocal tariff increases for 90 days.

*The Scope Macroeconomic Council brings together credit opinions from ratings teams across multiple issuer classes: sovereign and public sector, financial institutions, corporates, structured finance and project finance.

Brian Marly, a senior analyst in the Sovereign and Public Sector group, contributed to this research.

Stay up to date with Scope’s ratings and research by signing up to our newsletters across credit, ESG and funds. Click here to register.