Announcements

Drinks

Private credit: singular risks but also opportunities for Europe with capital-markets reform

By Karl Pettersen, Corporates, Scope Ratings

At the level of individual corporates, credit risk obeys the same rules in all markets, hence the universal value of credit ratings. No market is safe from companies going bankrupt.

Private credit extension fundamentally does entail more risk, for two reasons.

First, private lending is designed to cater to issuers that cannot access public markets. In the US, this largely comprises the lower tiers of non-investment grade corporates, rated B- or lower, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Secondly, opacity is the hallmark of private markets, which increases risk because it facilitates erroneous assumptions about credit quality. Indeed, opportunistic or unethical behaviour thrives in secrecy. As JPMorgan Chase Chief Executive Jamie Dimon’s described the problem following the First Brands failure, “When you see one cockroach, there are probably more.”

Dimon’s comment recalls economist John Kenneth Galbraith writing in the 1950s when he introduced the concept of “bezzle,” an inventory of embezzlement that accumulates in a country’s businesses and banks when money is plentiful. The long bull run in credit markets since the early 2010s has arguably created similar conditions today.

Europe remains characterized by multiple jurisdictions

So how vulnerable is Europe to this phenomenon?

SMEs are part of the backbone of the European economy, so the issue becomes the extent to which private creditors can identify and exploit the pockets of opacity and/or different underwriting standards in each market which are quite common inside and outside the EU.

That said, with private credit designed for regulatory avoidance, Europe remains far more regulated and bank-centric market than the US. American corporates rely on capital markets for roughly three quarters of their funding whereas in Europe, it is banks which provide around 75% of corporate funding.

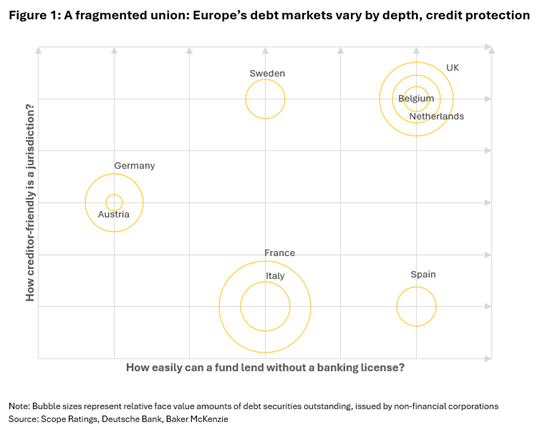

One reason why capital markets have developed less extensively in Europe than in the US is the region’s heterogeneity: differences in credit risk, legal protection and market liquidity across jurisdictions.

Private credit segment grows in Europe despite heavy reliance on banking sector

However, private credit is growing in importance even in Europe. The combined EU and UK direct-lending market was worth around EUR 440bn in mid-2025, surpassing the market for high-yield corporate bonds (EUR 415bn) and leveraged loans (EUR 310bn), according to Apollo Global Management. To date, most private credit activity is concentrated in Western Europe, typically as a supplement to traditional lending for large deals. However, as lenders seek higher returns, the segment is to set to get bigger.

Research by Morgan Stanley indicates that 75% of US middle-market transactions are financed through private credit, compared with roughly 50% in Europe. Yet Europe offers a more favourable risk-return profile partly driven by higher complexity and lower competition for capital. These conditions point to continued, rapid growth, with lending to SMEs in focus, mirroring the US experience.

Growth in direct lending points to difficult trade-offs in Europe’s capital markets

This expansion in private credit highlights a series of delicate trade-offs in Europe in contrast with the US.

There, while private credit market can create more losses, the overall market is likely sufficiently broad and deep to absorb them in a process of creative destruction in which capital is optimised, M&A and hybrid financing flourish, and the market deepens. Private credit ideally ensures that lending risk is spread out and churned in a vast, diverse market.

In Europe’ s less liquid and homogeneous market, there is less capital velocity and less room for rapid-fire refinancing which can hinder market growth and limits potential for risk dispersion as deal volume increases.

In essence, the European market is not naturally suited to a US-style private credit, so may remain relatively small while the risk cannot be diversified the same way. This may lead to more focused pockets of loss particularly in weaker markets, needing greater intervention by the authorities in the absence of immediate market remedies.

Europe’s default experience already points to significant differences in default rates between countries, with an overwhelming concentration of defaults among SMEs and a trend towards more business consolidation.

Private credit is just one manifestation of a need for a more cohesive and fluid capital markets union in the EU, a notion that continues to gain political traction for geopolitical and pragmatic reasons – take German Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s renewed call for the creation of a single European stock exchange – but faces considerable regulatory inertia across jurisdictions.

Simply put, the huge investment challenges facing Europe today — energy, defence, digital, environmental – requires capital to be mobilised quickly, cost effectively, and at a continental scale with efficient risk allocation. Achieving this is not feasible if European corporates remain reliant on fragmented lending by banks across dozens of different jurisdictions.