Announcements

Drinks

Egypt: current account pressures grow as rate hikes, inflation make IMF support more urgent

.jpg) By Thomas Gillet, Associate Director, Sovereign Ratings

By Thomas Gillet, Associate Director, Sovereign Ratings

Egypt’s vulnerability to tighter financing conditions stems in part from the prevailing pressure on its external accounts (external financing requirement of around USD 30bn in 2022) from the Covid-19 pandemic – which reduced tourism revenue and remittances among other factors – and the acceleration of inflation this year. Repercussions of the war in Ukraine has pushed prices higher still, increasing the cost of imported food and fuel. These pressures are common to several emerging market economies, particularly in Africa.

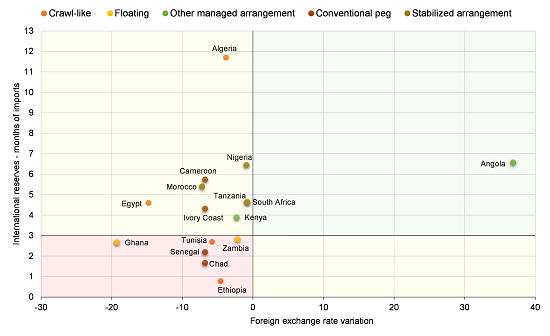

The recent 50bps interest rate increase of the Federal Reserve comes as many low to upper-middle income countries have limited options to fund higher gross external financing needs. Depreciating exchange rates of African countries have led to declining foreign exchange reserves, as measured by the number of months of import cover. This is particularly the case for countries without significant oil and gas exports (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Looking exposed: exchange rates and import cover for selected African countries

Note: IMF forecasts for international reserves in 2022.

Foreign exchange rate variation from January 1st to May 1st against the US dollar.

Source: Macrobond, IMF, Scope Ratings

While Egypt carries moderate gross external debt of around 33% of GDP, the country is highly sensitive to global monetary policy tightening because of large and persistent current account deficits (around 4% of GDP per year on average) linked to its structural reliance on food and energy imports. Higher prices (wheat, oil) are expected to have a long-lasting impact on the cost of imports, which could exceed USD 100bn (or more than 20% of GDP) in 2023 or about twice the 2000-18 average.

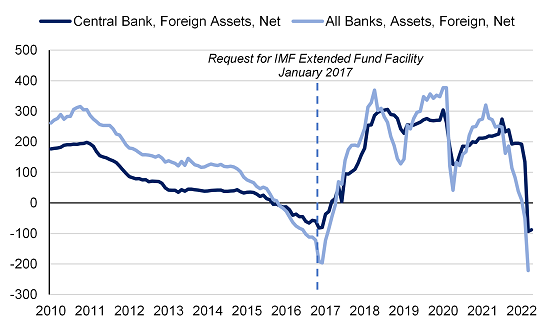

This vulnerability to an appreciating US dollar is illustrated by large non-resident capital outflows that have intensified recently. Net foreign assets turned negative in February-March 2022 for the first time since 2016-2017, when the authorities requested IMF financial assistance (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Egypt’s foreign capital outflows, 2010-2022

EGP bn

Note: Central Bank’s net foreign assets are mostly deposits in local banks; as of-end April 2022.

Source: Macrobond, Central Bank of Egypt, Scope Ratings

Despite large foreign capital outflows, Egypt still has some room to manoeuvre to fund external imbalances, helped by growing exports of natural gas to Europe, a planned privatisation programme, continued remittance flows and successful diversification of its debt financing with a recent USD 500mn Samurai bond issue.

Nonetheless, foreign liquidity conditions remain challenging. Adverse market conditions make it more difficult for launching new Eurobonds, Sukuk, or green bonds despite Egypt’s recent inclusion in the J.P. Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index.

The Egyptian Central Bank will likely try to clamp down on inflation by further increasing its policy rates (11.25%-12.25%) in response to an inflation rate (13.1% YoY in April) above its target range (7% on average ±2 percent). A rate hike would also ease downward pressures on the Egyptian pound while limiting the drawdown of foreign exchange reserves.

Still, shoring up Egypt’s external finances will require IMF financial support, which is likely to be premised on additional exchange-rate adjustments to avoid unsustainable use of foreign exchange reserves to defend the pound. A weaker pound would support export competitiveness and contribute to medium-term balance-of-payments stability. However, there are inevitable political and social costs to further currency depreciation if it worsens food and energy inflation and sets back growth given Egypt’s high level of poverty.

Negotiations between the Egyptian authorities and the IMF could last longer than expected, since calibrating the assistance package – macro-fiscal assumptions, financing envelope, upper-credit tranche conditionality, and mitigating measures – will prove more challenging than usual.

Even so, the approval of an IMF supported programme in coming months is likely, considering the successful implementation of the previous arrangement and good relations that the authorities have with the IMF. Egypt has one of Fund’s largest exposures after Argentina. Renewed IMF cooperation would be favourable for Egypt’s external outlook by containing foreign capital outflows, gradually building up foreign exchange reserves and supporting resilience through the cycle.

Conversely, no deal with the IMF within a reasonable timeframe would aggravate external risks, forcing the authorities to tighten capital controls and seek extra support from bilateral partners. In this scenario, persistent pressures and increasingly scarce foreign liquidity, with potentially more limited financial support from the Gulf Cooperation Council, will have negative credit implications for Egypt.

Thibault Vasse, Senior Analyst, and Brian Marly, Associate Analyst, contributed to this commentary.