Announcements

Drinks

Germany: emergency energy, military funding pressures debt brake, future spending flexibility

By Eiko Sievert, Director, and Julian Zimmermann, Senior Analyst

Germany’s federal government (AAA/Stable), which ran budget surpluses averaging 0.5% of GDP between 2014 and 2019, will not be returning to similar surpluses in coming years, due to its large spending commitments and a bleaker near-term growth outlook due to the energy shock.

The increased use of special funds weakens Germany’s previous record of fiscal transparency and risks weakening the fiscal framework. Future governments will face difficult fiscal policy decisions as it will become increasingly challenging to adhere to the current debt brake.

Berlin’s recently announced plan worth up to EUR 200bn (about 5% of GDP), financed through the Economic Stabilisation Fund (ESF), to lower gas and energy prices brings the country’s total support measures to shield households and businesses from the energy crisis to EUR 295bn (7.6% of GDP). It includes the recent announcement of directly subsidising gas bills in December and the introduction of a gas-price brake from March 2023.

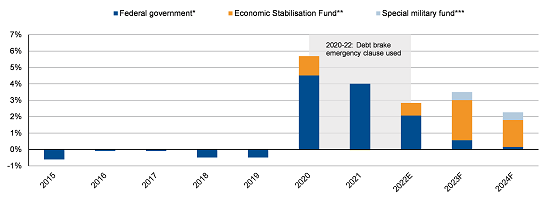

Figure 1: Federal government net debt issuance

% of GDP, central government debt issuance, net of redemptions

Notes: * Assumed to borrow 0.35% of GDP per year, plus a cyclical component.

** ESF net borrowing from 2023 assumed only for the announced EUR 200bn energy package. Net borrowing assumed at EUR 30bn for 2022, EUR 100bn for 2023 and EUR 70bn for 2024.

*** Special military fund (EUR 100bn of borrowing authorisations) net borrowing assumed at EUR 20bn per year, starting from 2023.

Sources: Bundesfinanzagentur, Bloomberg Financial L.P., Destatis, Frühjahrsprojektion 2022 der Bundesregierung, Scope Ratings

This represents the biggest support package of any European country surpassing even the United Kingdom’s (6.5% of GDP) and will ensure significantly larger-than-expected net issuance of German government debt in the years ahead. The additional borrowing comes on top of the EUR 100bn special fund for the federal armed forces announced earlier in the year.

To finance these significant multi-year programmes, the Scholz government has announced debt-funded extra-budgetary “special funds”, allowing for future expenditures effectively outside of the debt brake, which limit the budget deficit to a maximum 0.35% of GDP.

We estimate redemption costs related to exceptional borrowing and the special funds announced since 2020 to reach up to 0.45% of GDP by 2028. This would entirely exhaust the deficit limit under the federal debt brake.

Net bond issuance to jump with near EUR 300bn in emergency spending

Germany has ample fiscal space, the debt brake aside, for such large fiscal programmes. We expect net borrowing will average up to 3.7% of GDP between 2020-24, in stark contrast to pre-pandemic central government surpluses and despite the debt brake binding again next year (Figure 1).

The bigger challenge is managing future redemption costs. Debt incurred under the emergency clause of the debt brake in 2020-22 will be redeemed from 2028 over 30 years, a self-imposed commitment in line with the constitutional requirements.

Those costs are not insignificant, equivalent to up to EUR 12bn (0.25% of GDP), before considering repayment of debt incurred under the military and energy special funds. Those costs could amount to around EUR 10bn (0.2% of GDP) if we assume full utilisation of the funds and a similar redemption timeline of 30 years. Together, these costs will amount to around EUR 20-25bn from 2028 onwards, exhausting the 0.35% of GDP available for annual debt financing.

Slower growth and higher borrowing pose medium term challenges

A historically high reliance on Russian energy, amplified by an export-oriented economy, makes Germany one of the most exposed countries to the repercussions from Russia’s war in Ukraine. We now expect economic growth to slow to 1.4% in 2022 and contract by 0.2% in 2023.

Longer term, we see additional pressure on future budgets from Germany’s ageing population. The European Commission 2021 Ageing Report calculates those age-related costs, predominantly on pensions and healthcare, will increase by 1.5pp of GDP until 2030, from 23.3% of GDP in 2019 to 24.8%, assuming no reforms are undertaken.

The combination of pandemic-related debt, spending through special funds and increasing age-related costs could amount to almost EUR 100bn per year by 2030, or 2% of expected GDP. This will make it increasingly challenging for future governments to comply with debt brake limitations on the federal budget.

Discussions between the European Commission (EC) and member states on reforming the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact are ongoing. Germany’s extensive use of its fiscal space has attracted some condemnation in other European capitals and the rising fiscal challenges to future German governments could soften the country’s past opposition to the EC’s reform proposals.