Announcements

Drinks

Q&A: how will the ECB's efforts to trim its balance sheet affect European banks?

By Chiara Romano, Associate Director, Financial Institutions

By Chiara Romano, Associate Director, Financial Institutions

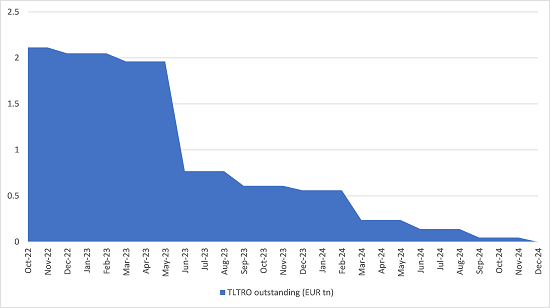

On top of around EUR 5trn of securities acquired in bond purchase programmes, the ECB has around EUR 2.1trn in long-term refinancing operations. Attractive TLTRO terms saw banks take up significant amounts. The largest drawdown was EUR 1.2trn in TLTRO III.4, which settled in June 2020. By comparison, before TLTRO III was introduced in 2019, lending related to monetary policy operations stood around EUR 620bn.

What is the benefit to the banking sector?

The preferential rate on TLTROs – at the maximum equal to the deposit facility rate minus 50bp – ended in June 2022, but banks still benefit from past negative rates. On the current outstanding TLTRO, the interest that banks pay is the average of the Deposit Facility Rate (DFR) over the lifetime of the respective operation. As of today, we estimate that at around negative 42bp, meaning close to EUR 9bn of interest income from TLTRO funding for banks.

On top of that, when the DFR turned positive, the ECB abandoned the two-tier mechanism that had been used to exempt a multiplier of the banks’ minimum reserves from negative rates. The end of tiering meant that excess liquidity was remunerated at 75bp (the DFR), adding an extra EUR 35.3bn of interest paid to banks. That adds up to a total of EUR 44bn of interest paid by the ECB to banks.

The current stance, where banks receive the benefit from negative rates on TLTRO while also earning on excess liquidity seems, reasonably, to be an unnecessary subsidy to the banking sector.

Central banks have negative carry and the risk of their reserve buffers coming under pressure is rising. In an extreme scenario of reserves falling below minimum requirements, governments would be responsible for injecting fresh capital. Such a move would be highly unpopular politically at a time when government budgets are already stretched.

How can this be corrected?

The ECB is expected to come up with a decision at its next meeting on 27 October. But the design of any operation to absorb liquidity greatly depends on the aim.

If the primary goal is to reduce direct profits from TLTRO, changing the terms of current operations is a possibility. We see this as a drastic move, though. Leaving aside legal uncertainties, we highlight the risks that such a solution could create for the credibility of future TLTRO operations. TLTRO has proven to be an invaluable tool to support lending in difficult environments and stave off deflation risk.

Given the short remaining duration of the current lines, retroactively changing the terms would be unnecessarily harsh. As a reminder, the bulk (TLTRO III.4, around 60% of current outstanding) matures in June 2023.

Outstanding TLTROs (EUR trn)

Source: ECB

If, by contrast, the ECB focuses on limiting profits from excess liquidity on a structural basis (at the same time providing an incentive for early repayment of TLTRO) it could reintroduce a form of tiering where only a portion of excess liquidity is remunerated or a portion is exempted from remuneration. Fine-tuning such a mechanism would have to consider several aspects, including risks to the proper functioning of short-term money markets.

One possibility would be to link the portion exempted from remuneration to the TLTRO balances of individual banks, effectively limiting banks’ ability to directly arbitrage the central bank’s balance sheet. This option would weigh more heavily on banks that are net borrowers from the central bank, such as Italian banks. However, this latter option could undermine the future effectiveness of the ECB’s TLTRO tool, validating old fears that TLTRO take-up would carry negative consequences under some circumstances.

Are there any other possibilities?

One option would be to offer banks the possibility to roll over their TLTRO III balances into new three-year lines, not tied to lending targets and with more punitive conditions. This would allow the ECB to fix the LTRO tool for the future, retaining it in the toolkit to address funding shortages but reducing the potential for banks to arbitrage its balance sheet. Probably not every bank would accept giving up the near term profitability boost embedded in current lines, but some would value the optionality on funding such an option would provide, especially given the uncertain macro environment.

We believe this would be a low-risk option for the ECB with wins on both sides. More importantly, it would also normalise LTRO as a tool to support bank funding, not profitability, by reinstating the incentive for banks to return to private-sector funding when available at reasonable cost.

Do banks need central bank funding?

That depends on wholesale funding market conditions. Current liquidity metrics are very reassuring but we know that they are inflated by the ECB’s balance sheet, having taken a significant role in maturity transformation as a by-product of its monetary policy. As the ECB normalises, Liquidity Coverage Ratios will decline and banks will have to increase borrowing from the private sector.

Extending LTROs would means that wholesale markets would benefit from funding security over a term longer than the current end of 2024, avoiding any near-term cliff effects at a time of macro volatility and rising rates. For banks in peripheral Europe, where banks’ wholesale funding costs are under pressure from rising sovereign spreads, it would provide a safe (albeit costly) shield to increased market funding costs.