Announcements

Drinks

Germany: medium-run post-pandemic recovery to lag AAA peers, even as near-term pressures ease

By Julian Zimmermann, Senior Analyst, Sovereign Ratings

By Julian Zimmermann, Senior Analyst, Sovereign Ratings

The sluggish longer-term growth outlook contrasts with the likelihood that Europe’s largest economy will experience a mild recession at worst in 2023, a better outcome than expected by most a few months ago. Credit goes to a raft of measures by the federal government, swift adaptation by German industry and consumers to high energy prices and diminished imports of Russian gas, as well as mild winter weather.

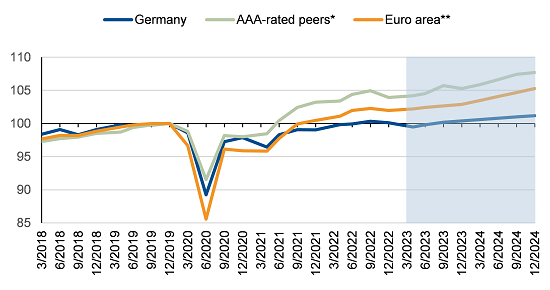

At the same time, Germany’s economic output has recovered to pre-pandemic levels much more slowly than euro area and peer economies (Figure 1). The trend is set to continue. By the end of 2024, we expect the German economy to only be around 1.2% larger than at the end of 2019, compared with 5.7% for the euro area and 7.7% on average for other AAA-rated countries.

Germany’s drag on growth in Europe will continue at least until 2030, putting strain on the country’s strong public finances given accumulating costs related to the pandemic, the war and the energy transition.

Figure 1: Mind the gap: Germany’s post-pandemic growth trajectory

Quarterly real GDP, Q4 2019=100

* Simple average for Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. Growth projections from Scope’s 2023 Sovereign Outlook.

** Linear quarterly growth assumption for 2023/24, based on yearly growth projections from Scope’s 2023 Sovereign Outlook.

Source: Destatis, Eurostat, Scope Ratings

Immigration reform shows government willingness to tackle long-term challenges

Addressing the structural change that Germany needs to boost growth is politically challenging, but first steps are being taken. This includes a proposed overhaul of immigration laws, including allowing dual citizenship of non-EU citizens, and easing of rules for immigration of highly skilled workers in recognition of the country’s ageing population and shrinking number of people of working age, estimated to decline by around 0.8% per year between 2023-30.

We have also highlighted the investment gap, equivalent to around EUR 410bn as of 2021, which will be equally challenging and costly to narrow in coming years given tighter financing conditions. Germany has experienced persistent underinvestment coupled with slow project implementation, yet investment needs are at a record high to support the country’s energy-intensive manufacturing sector in its green and digital transition.

These challenges provide the backdrop for Germany’s current weak economic performance. Despite the relatively moderate quarterly downturn in Q4 2022 and the more benign energy supply position, we are sticking to our view of a 0.2% contraction in 2023. This contrasts with the recent revisions by the IMF (0.1%, from -0.3%) and the German government (0.2%, from -0.4%), and mainly reflects our expectation of tighter financing conditions curbing investment and private consumption. These effects will only be partially balanced by improving terms of trade and rising external demand from China as it loosens pandemic restrictions.

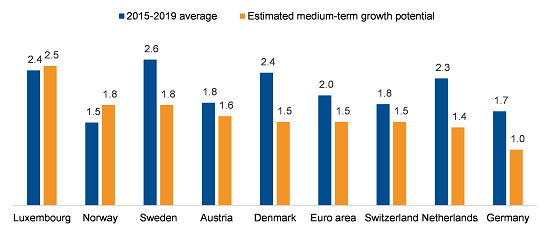

Figure 2: Germany’s medium-term growth prospects vs AAA peer countries

Annual real GDP growth rate, %

Source: Eurostat, Scope Ratings

Sustained fall in energy prices would boost economy, public finances

Germany’s near-term economic performance is also being stabilised by substantial fiscal support, due to be phased out during 2024. The German federal government has enacted several relief packages, the costliest of which are a gas and electricity price break for households and businesses, budgeted to cost EUR 83.3bn (2.1% of expected GDP) in 2023. However, under the assumption that current, lower-than-anticipated gas and electricity prices are sustained over 2023, the measures might end up just costing around half of the amount budgeted.

Longer-term, as fiscal support is withdrawn due to a political commitment to comply with debt-brake borrowing limitations as crisis spending abates, we estimate Germany’s growth potential at around 1% per year in the coming years, the lowest among its peer group (Figure 2), and 0.1pp lower than we projected a year ago.

Towards the end of the decade, the rate is estimated to further decline to around 0.5-0.75% by several economic research institutes, as the ageing trend accelerates. This compares to a relatively robust 1.7% growth observed in the pre-pandemic period from 2015-19.