Announcements

Drinks

France and Spain take different paths on pension reform; demographic challenges remain

By Jakob Suwalski, Director, and Brian Marly, Analyst, Sovereign Ratings

While the Spanish government was able to achieve consensus over pension changes, the French government failed to secure an absolute parliamentary majority to back its reforms, which were opposed by trade unions and led to mass protests and strikes.

The substance of the reforms is different. France (AA/Stable) aims to rebalance its pension system by increasing the legal retirement age from 62 to 64 while requiring longer contributions for a full pension. In contrast, Spain (A-/Stable), whose legal retirement age is set to increase to about 67 by 2027, focused on increased contributions from corporates and younger workers, including alternative calculations of pension amounts and an increase in the Intergenerational Equity Mechanism (IEM) tax.

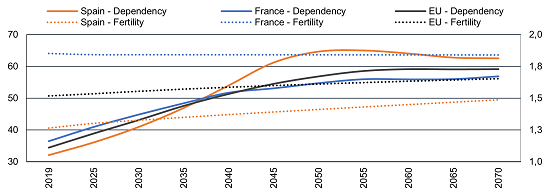

Yet the challenge is fundamentally similar: meeting the inevitable increase in the cost of providing retirement income in countries with tax-funded pension systems where the gap between the proportion of adults of working and retirement age is widening (Figure 1).

The reforms in both countries represent only incremental overall improvements, increasing longer-term fiscal pressure in the case of Spain and having only a marginal impact for France, while offering no immediate solution to the problem of chronic under-employment of older members of the workforce – hence the need for deeper reforms.

Figure 1 – Demographic pressures in Spain more intense than France

Old-age dependency ratios (LHS), fertility rates (RHS)

Source: European Commission 2021 Ageing Report, Scope Ratings

High pre-retirement age unemployment characterises French, Spanish economies

France and Spain have aging populations and sub-replacement birth rates, though the intensity of the pressures differs. In Spain, the population is ageing rapidly, while the fertility rate is one of the lowest in Europe, leading to a shrinking workforce and a growing elderly population hence a strain on the pension system, which is in deficit. In contrast, France's population ageing is more gradual, primarily due to a higher fertility rate.

France and Spain stand out for their very low levels of employment among older workers. As of 2021, employment rates for workers aged between 55 and 64 stood below 56% in both countries, against an average of about 61% in the euro area.

Spain’s priority in its pension reform was to benefit the most vulnerable, such as those with irregular professional careers, and avoid cuts in pensions for young people through a progressive increase in the ceiling for maximum contributions and creating a solidarity fee. The reforms include an alternative calculation for pension payments which extends the computation to 29 working years, with the 24 worst-paid months discarded.

These measures require a significant increase in pension spending over the coming decades without boosting contribution income, despite some offsetting measures: a freeze in maximum pensions, incentives to delay retirement, the introduction of a solidarity tax and the doubling in the IEM tax rate to 1.2% by 2029.

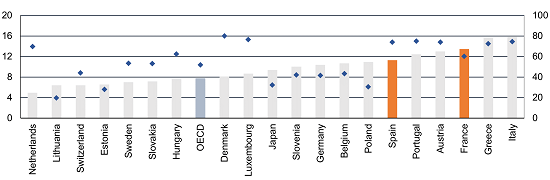

Figure 2 – Pension expenditures in Spain and France are among the highest in the OECD

Public pension spending, % of GDP (2019, LHS), gross pension replacement rate (men, 2020, RHS)

Source: OECD, Scope Ratings

Spain’s pensions deficit set to widen; doubts over eliminating France’s

Spain’s total public spending on pensions will rise steadily after its reform to 16.2% of GDP by 2050 from 13.6% in 2021, according to a report from independent fiscal watchdog AIReF. Over the same period, the structural deficit of the pension system will rise by about 1.1 pp of GDP, above government estimates of a more benign 0.3 pp increase. Higher social security contributions fall mostly on companies, which may in turn weigh on job creation and wage growth.

In France, the recently adopted reform could be insufficient to close the financing gap of the pension system, according to recent estimates from think tank Rexecode, judging government forecasts to be too optimistic. Net fiscal gains resulting at a moderate 0.6% of GDP by 2030 would leave the pension system in a deficit of between 0.2% and 0.6% of GDP. Exemptions have diluted the impact of extending the retirement age, so most gains would stem from increased fiscal receipts based on assumptions of higher medium-term growth and increased employment.

While we see less fiscal urgency for further pension reforms in France than we do in Spain, the question is whether the lack of political consensus over the reforms just enacted will hold back the French government’s attempts at other structural reforms – and whether Spain can further exploit its consensus to strengthen its pension system.

Access all Scope rating & research reports on ScopeOne, Scope’s digital marketplace, which includes API solutions for Scope’s credit rating feed, providing institutional clients access to Scope’s growing number of corporate, bank, sovereign and public sector ratings.