Announcements

Drinks

Germany: strict debt-brake application fosters discipline but EUR 300bn investment lag remains

By Eiko Sievert, Sovereign and Public Sector

Germany’s constitutional court ruling on 15 November 2023 regarding the reallocation and repurposing of funds, initially intended to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic, to the Climate and Transformation Fund underlines the country’s strong commitment to fiscal discipline. However, it also reduces budgetary flexibility to reallocate and repurpose borrowed funds over multiple years. The court’s decision thus reinforces the applicability of the constitutionally anchored debt brake rule by setting clear boundaries on the use of extrabudgetary funds.

The coalition government now faces difficult discussions on how to balance current spending commitments with funding Germany’s energy transition and meeting EU climate goals, not least given doubts about the legitimacy of other recent off-budget funding initiatives.

Modest near-term budgetary impact

To be sure, the immediate, direct impact of the constitutional court decision is manageable. The credit authorisations that have been annulled by the court amount to EUR 60bn (1.5% of GDP in 2022), which were due to be spent by 2027. Assuming equal allocation over four years, this implies a funding shortfall of about EUR 10-20bn per year implying downside risks to spending plans beyond 2024 and therefore Germany’s growth outlook.

Besides this credit authorisation, the affected Climate and Transformation Fund also has reserves and regular inflows from greenhouse gas emissions trading schemes. Between 2024 and 2027, total spending of EUR 211.8bn, or around EUR 53bn per year, was earmarked to fund various green initiatives and investments, which have now been partially frozen by the government in response to the court ruling until priorities are reconsidered.

Wider repercussions from court ruling could reduce public investments

However, the arguments on which the constitutional court based its decision* imply stricter rules and greater scrutiny on similar budgetary practices used by the Bund for other special funds, and Germany’s 16 federal state governments. Notably, these have also set up special funds during the Covid-19 pandemic and increasingly allocate unused funds to tackle long-term challenges such as the energy transition.

The judgement thus adds uncertainty to the viability of current budgetary practices at the federal and state level, and could dampen the investment outlook in the near term, weighing on Germany’s already weak growth outlook.

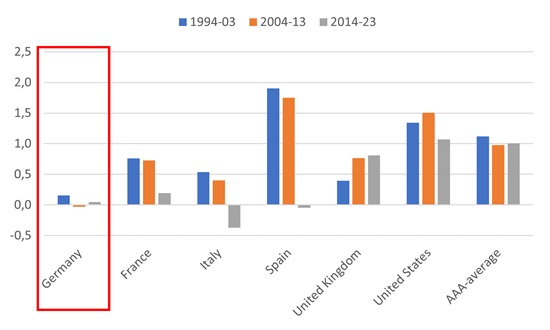

Germany’s net fixed capital formation from the public sector averaged just 0.1% of GDP a year over the past three decades, far lower than other AAA-rated economies (1.0%), and behind other large economies such as the United States (1.3%), Spain (1.2%), the United Kingdom (0.7%), France (0.6%) and Italy (0.2%). If investments had been in line with AAA-rated economies, Germany’s government would have invested an additional EUR 303bn over the past decade.

Figure 1: German public sector investments have lagged behind for decades

Net fixed capital formation, general government, % of GDP

Source: European Commission, Scope Ratings

Note: AAA-rated countries include Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland

Decision could impact domestic and European fiscal rules

The court’s ruling will likely reignite discussions around reforming the debt brake rule to address investment needs required to meet Germany’s ambitious green transition targets. Fundamental reform of the debt brake requires a two-thirds majority in parliament, and hence support from the opposition CDU/CSU party, which is unlikely in the near term. Tensions are therefore likely to increase between the coalition partners, in particular the Green Party and the more fiscally conservative Liberal Democrats, as spending priorities now need to be reassessed.

The ruling is also likely to affect the final negotiations of the forthcoming EU fiscal rules as it highlights the trade-off between enforcing strict fiscal rules and maintaining budgetary flexibility to address emergencies as well as investment needs.

We expect general government debt as a share of GDP to fall below 60% by 2027. This implies that Germany has some fiscal space to increase investments. With the country’s rapidly ageing population and shrinking growth potential, policymakers will need to focus more on enhancing the country’s future competitiveness to avoid storing up long-term fiscal imbalances.

*First, the court found that the government did not demonstrate a sufficiently strong link between the emergency response to the pandemic and the new uses of the credit authorisations. Secondly, the planned use of credit authorisations was due to happen too long after the pandemic had ended. Finally, the second supplementary budget was passed only in early 2022, making retrospective adjustments to the 2021 budget a violation of budgetary principles.

Access all Scope rating & research reports on ScopeOne, Scope’s digital marketplace, which includes API solutions for Scope’s credit rating feed, providing institutional clients access to Scope’s growing number of corporate, bank, sovereign and public sector ratings.