Announcements

Drinks

Baltic update: divergence in macro-fiscal outlooks drive recent rating actions

By Brian Marly, Sovereign and Public Sector

Over the past 12 months, we have downgraded Estonia to A+/Stable (from AA-), assigned a Positive Outlook to Lithuania’s A rating, and affirmed Latvia’s A-/Stable rating. We see rating convergence between Lithuania and Estonia and a growing credit-rating gap between them and Latvia.

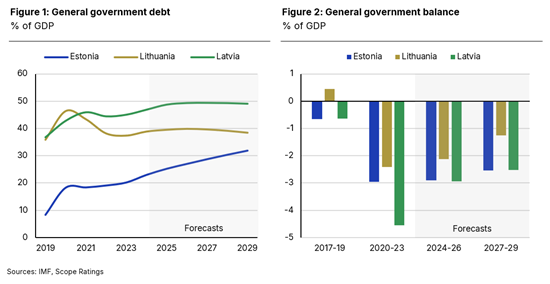

Baltic governments continue to display some of the lowest public debt ratios in the euro area, but differences in fiscal policies are helping put debt trajectories on divergent courses in the context of the three countries’ more uneven economic performance.

For small, open economies, such divergence points to differing degrees of resilience should geopolitical risks related to Russia’s war in Ukraine increase in the months ahead amid uncertainty over US trade and foreign policy under a new Donald Trump presidency.

Estonia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is forecast to increase steadily to around 32% by 2029 while Latvia’s will remain broadly stable around 50%. We expect Lithuania’s debt-to-GDP will resume a gradually declining trend in the medium term to around 38% (Figure 1), thus taking a more positive view relative to latest government forecasts of a progressive rise in indebtedness.

Higher defence spending, interest costs pose common fiscal challenges in region

Fiscal deficits in the Baltics have risen over recent years from the impact of recent shocks and persistent inflation-related spending pressures. In addition, the heightened geopolitical tensions in eastern Europe have a durable budgetary impact as the governments spend more on defence, at around 3%-4% of GDP annually.

Direct military risks related to Russia’s war in Ukraine remain low due to the Baltic’s international alliances, but the countries’ proximity to Russia exposes them to spillover effects from the conflict, including broader security challenges such as cyber risks and disinformation campaigns. The Baltic countries are relatively well prepared compared with the rest of Europe, but a protracted conflict adds significant uncertainty to the medium-term fiscal outlook.

Moreover, high interest rates, though set to decline gradually, will also drive an increase in interest payments across the region. We estimate net interest payments to increase to around 1.5-3.0% of revenue in 2024-29, from 0.5-1.5% in 2023.

Estonia’s fiscal balance will improve only gradually, reflecting a weak economic momentum and structural spending increases (notably on education and social policy). The government deficit is expected to remain elevated at 3.1% of GDP in 2024 and 2.9% in 2025, though improving from previous estimates thanks to the implementation of additional consolidating measures (Figure 2).

Similarly, we expect Latvia’s fiscal deficit to remain elevated at 3.1% of GDP in 2024 and 3.0% of GDP in 2025, with revenue-side pressures from the implementation of a labour tax reform next year.

Lithuania’s fiscal deficit is set to widen in 2025 to 2.5% of GDP (up 0.6pps from 2024) due to spending pressures from indexation mechanisms and fiscal stimulus for the economy, before declining in subsequent years on strong growth in tax revenue.

Lithuania’s growth prospects diverge from Estonia’s and Latvia’s

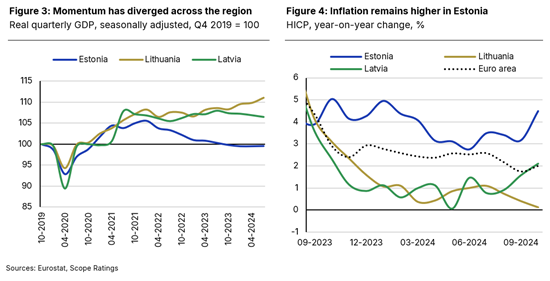

Indeed, Lithuania’s economy has outperformed its neighbours, with growth estimated at 2.3% this year, and expected to rise to 2.9% in 2025 as private investment recovers and household consumption remains robust.

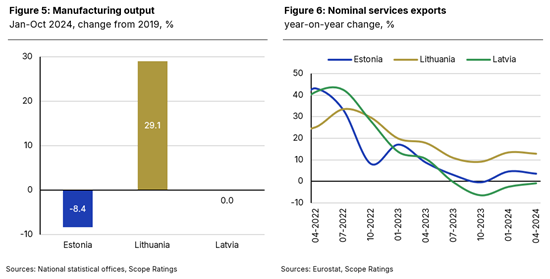

Manufacturing activity in Lithuania is experiencing a robust rebound (Figure 5), in part reflecting closer ties to Poland (A/Stable), whose economy has turned out to be among the fastest growing in Europe in 2023-24. Conversely, Estonian and Latvian manufacturing have suffered from the exposure to the weak Finnish and Swedish construction markets.

Lithuania’s economic recovery has also been driven by buoyant services exports (Figure 6), reflecting a structural transition away from low-tech manufacturing towards high value-added services including financial services and IT.

Conversely, Estonia fell into a prolonged recession since 2022. Output contracted by an estimated 0.9% in 2024 and will recover only gradually, with growth forecast at 1.6% next year, as tax rises will likely hold back a tentative recovery in private demand.

In Latvia, the economy made a rapid recovery after the pandemic but has since stagnated, set to shrink by 0.2% this year, down from a previous estimate of 1.6% growth after large positive data revisions for 2023 GDP. Improving consumption should still drive a recovery next year, with growth forecast at 1.5%.

Improving external demand should support growth across the region in 2025, though the risk balance remains tilted to the downside on account of the fragile euro area economic outlook and uncertainties around global trade. External competitiveness will remain a key concern for all Baltic economies amid high nominal wage growth. Estonia’s export performance has been hit particularly hard by competitiveness pressures, as underlined by recent IMF estimates.

Declining interest rates support near-term growth prospects

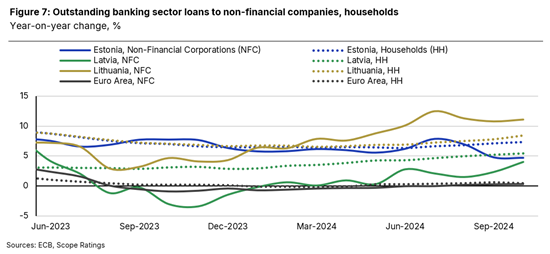

Loosening financing conditions across the region should also support domestic demand in the near term, especially as very low leverage (particularly in Latvia and Lithuania) leaves households and corporates with significant headroom to borrow.

Credit growth has already picked up in Lithuania (Figure 7) amid strong business and household confidence and declining borrowing costs, which should support a recovery in private investment next year. In contrast, credit extension to the private sector is still subdued in Latvia, reflecting long-standing barriers to finance.

The recent lifting of US sanctions after a successful regulatory overhaul of the Latvian banking sector with healthy banking sector balance sheets, should favour a pick-up in lending. The establishment of a regional hub of the Nordic Investment Bank (AAA/Stable) in Riga is a sign of confidence. However, we see risks that the introduction of a new levy on banks’ net interest income will constrain credit supply, despite the inclusion of rebates that aim to raise lending volumes.

Stay up to date with Scope’s ratings and research by signing up to our newsletters across credit, ESG and funds. Click here to register.