Announcements

Drinks

Poland: political polarisation, high deficits strain fiscal flexibility; growth remains resilient

By Jakob Suwalski and Elena Klare, Sovereign and Public Sector

Poland’s (A/Stable) structurally high spending on debt service, defence, and social programmes leave limited room for fiscal consolidation in the absence of political consensus. The outcome of the recent presidential election, which maintained the executive divide between the opposition-aligned president and the centre-right, pro-EU government, reinforces the risk of legislative deadlock, reducing the likelihood of progress on meaningful fiscal reform.

While Poland’s public finances are solid given its still-moderate debt-to-GDP ratio of 55.3% in 2024, its fiscal space has narrowed significantly, with an increasing share of government revenues committed to non-discretionary spending.

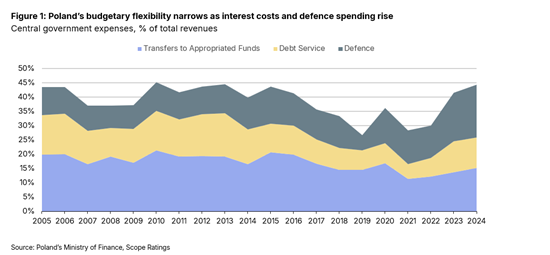

In 2024, nearly 45% of central government revenues were pre-committed to debt service, earmarked transfers (mainly Social Insurance Fund and Pension & Disability Fund), and defence spending. Debt service costs have more than doubled since 2021, rising to 11% of revenue from 5%, while defence spending has surged to 19% of revenue – the highest share since Poland’s transition to a market economy (Figure 1).

These rigidities significantly reduce the government’s budgetary flexibility. Compared with 2020, when Poland last recorded a deficit above 6% of GDP, the share of revenue available for discretionary use has shrunk by around 8 percentage points, reflecting the growing structural nature of public expenditure. Since 2021, this constraint has intensified, with pre-committed spending rising by an estimated 16 percentage points of revenue.

Unlike pandemic-era spending, today’s fiscal pressures are thus likely to persist, not least because it will be difficult to reach consensus on spending cuts or tax increases.

Institutional divisions and policy gridlock weigh on fiscal consolidation prospects

While the government of Prime Minister Donald Tusk won a confidence vote on 11 June, ensuring some short-term political stability, it faces the risk of heightened friction within the governing coalition and the opposition of President Karol Nawrocki, who has veto powers on important legislation.

Planned fiscal measures for 2025 suggest limited scope for near-term consolidation, with estimated savings of just 0.2% of GDP, down from 0.4% in 2024. The government is now expected to advance legislative and budgetary initiatives, having previously delayed major adjustments pending the presidential election outcome, which constrained its near-term fiscal and policy agenda.

Rising spending on welfare and pensions is structural, and politically based spending commitments typically increase ahead of a general election, with the next one due in 2027. Fiscal consolidation is thus likely to rely on higher tax receipts supported by continued economic growth, reforms aimed at widening the tax base and improving collection. However, such reforms will require policy-making consensus and cross-party cooperation.

Debt increase nears legal thresholds

Despite these governance challenges, we expect Poland’s fiscal deficit to decline to around 3.4% by 2030, from 6.2% in 2025. We expect expenditure growth to moderate, while revenue will benefit from fiscal drag effects due to frozen tax thresholds and allowances, increasing the effective tax burden amid still-elevated nominal wage growth.

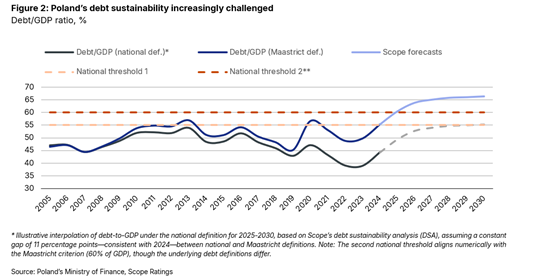

Public debt should thus rise gradually to around 66% of GDP by 2029 before stabilising in 2030 from 55.3% of GDP in 2024, using Europe’s Maastricht definition.

Critically, Poland’s long-term fiscal discipline is anchored by the Public Finance Act, which mandates spending constraints—including limits on deficits and wage growth—once the government’s definition of debt reaches 55% and 60% of GDP.

Historically, the gap between Poland’s debt in the national and EU definitions was around 2–3% of GDP, but it has widened to more than 10%, mainly due to post-pandemic spending outside the core budget through entities like the Polish Development Fund. Shifting more liabilities off the central government’s balance sheet has weakened the effectiveness of the constitutional safeguards. Still, we expect these to remain in place and anchor Poland’s long-term debt trajectory.

Robust growth anchored by EU integration and structural convergence

Similarly, Poland’s potential growth remains high at around 3%, supported by a competitive, diversified economy, favourable labour market, and productivity converging with that of higher-income EU countries. Poland has proved resilient to recent external shocks, including the energy crisis and supply-chain disruptions.

Poland’s economic growth remains robust and should average 3.1% over 2025-27, driven by EU funds and continued FDI. Poland is a top recipient of cohesion and recovery funds (EUR 137bn over 2021-27, or 16% of 2024 GDP) and benefits from a relatively strong absorption capacity.

EU funds are expected to contribute 1.1 percentage points to GDP growth in 2025, reinforcing the investment outlook and supporting long-term development goals. Moreover, the country continues to attract significant foreign direct investment, supported by a stable business environment and skilled workforce.

Still, a key risk for the country’s credit outlook is that delays in receiving EU funds hamper economic growth and weaken its public finances. Sustaining Poland’s growth and gradual fiscal consolidation thus depends on domestic reforms (in part linked to EU funds), political and macroeconomic stability, and continued constructive relations with EU institutions.

Scope’s next review date for Poland is 14 November 2025.