Announcements

Drinks

Germany: ambitious 2025-26 spending plans likely delayed, weighing on near-term growth

By Julian Zimmermann, Sovereign and Public Sector

We estimate that the favourable impact on German GDP from additional government spending will average around 0.3-0.4pps over 2026-2030, raising the annual real GDP growth to an average 1.2%.

This outlook, however, critically depends on a meaningful increase in public investment from 2026 onwards, even if actual spending falls short of government targets. Specifically, we assume that around half of the planned EUR 59bn in spending from the EUR 500bn special fund for infrastructure can be implemented in 2026, gradually rising to around EUR 40bn (0.92% of GDP) annually in subsequent years.

Risks to the outlook are significant. The potential for public-sector under-spending, with knock-on effects on private-sector investment, could constrain growth. Legal and administrative obstacles to fast-tracking investment add to the risks of delays. Moreover, much of the planned government investment could be spread over an extended time frame, diluting the near-and medium-term impact on growth.

For example, Germany’s federal states, the Länder, will receive EUR 100bn from the special fund for infrastructure but have until 2043 to fully disburse their allocations provided projects are agreed by 2036. The states are required to commit only one-third of total investments by 2029, highlighting the challenge of ramping up spending significantly in the near term.

Slow-moving investment spending would significantly weigh on the country’s growth prospects. This will compound existing structural challenges including a declining working-age population and adverse external factors, notably higher US tariffs and growing competition from Chinese producers.

Debt-to-GDP to rise more slowly than expected due to slower expenditure increases

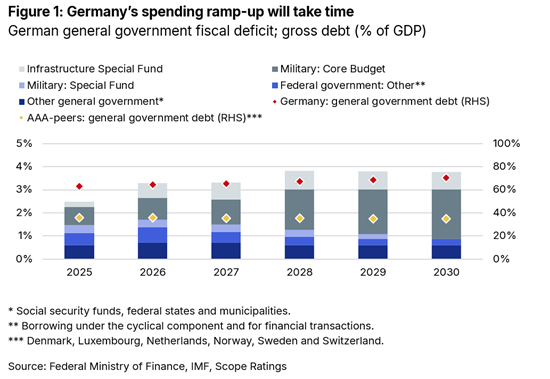

In our latest affirmation of Germany’s AAA/Stable ratings on 12 September, we revised our debt projections to account for a more moderate pace of fiscal loosening than previously assumed. We now see the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio increasing towards 70% of GDP in 2030 from around 62% in 2024. Previously, we projected the debt ratio to increase to around 74% by 2030. While still below the country’s historic peak of 81% in 2010, Germany’s debt ratio is relatively elevated compared with other AAA-rated countries, which had an average debt ratio of 36% in 2024, one expected to remain broadly stable in coming years.

Germany’s fiscal deficit for 2025 is likely to be 2.5% of GDP, down from 2.7% in 2024 despite the significant spending packages announced. This is partly because the 2025 federal budget was passed only on 18 September, leaving little time for implementation. For 2026-30, we expect higher spending on defence and the special fund for infrastructure, but still below government plans, resulting in projected fiscal deficits averaging 3.6% of GDP (Figure 1).

Significant additional fiscal loosening thus looks unlikely in the near term as the focus will be on the implementation of existing funds. Additionally, further constitutional changes to the debt brake appear difficult to implement, as the current government lacks the necessary two-thirds majority in the parliament, a constraint likely to persist given the current fragmented political landscape.

Revised German funding plan reflects moderately higher funding needs

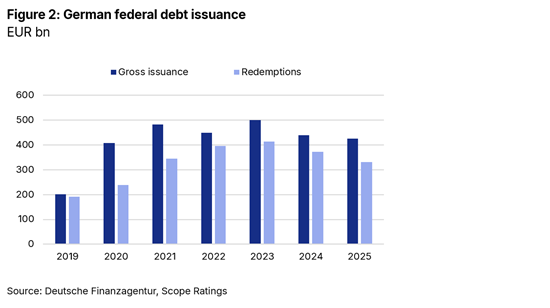

To fund the initial outlays under the new debt brake allowances, the Finanzagentur updated its funding plan for the final quarter of 2025, raising its annual funding target by EUR 15bn to EUR 425bn (Figure 2), after a similar increase of EUR 19bn in Q3. Despite the increase, this is the lowest level of gross issuance since 2021 but still marks an increase in net terms to EUR 94bn, from EUR 67bn in 2024.

Looking ahead, we expect Germany’s annual net funding needs to average around EUR 130bn for 2026-28, or around 2.7% of expected GDP.

Investment spending needs to be targeted, timely, and complementary

It will be vital to ensure that investments under the special infrastructure fund do not crowd out investment spending from the regular, core budget. To this end, the special fund law requires the share of investment in the core budget to remain above 10% of total spending, broadly in line with its level in 2024. However, accounting rules allow for ample flexibility, and ultimately the parliament decides whether the investment share is met, effectively handing control over this mechanism to the government.

The 2025 budget already reflects significant amount of reshuffling of spending items between the core budget and the infrastructure special fund. In particular, the budget of the Federal Ministry of Transport saw net spending reductions of around EUR 11bn according to calculations from the ifo Institute, which mostly reappear in the infrastructure special fund, while the budget for the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs saw a net increase of similar magnitude, mostly related to unemployment insurance. This highlights the government’s increased flexibility under the new budgetary framework, adding uncertainty to expected positive economic impact of the announced stimulus.