Announcements

Drinks

Russia faces uphill task to offset sanctions with closer BRICS+ financial, trading links

By Levon Kameryan, Associate Director, Sovereign Ratings

By Levon Kameryan, Associate Director, Sovereign Ratings

Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, which make up the BRICS group of developing economies, account for 40% of the global population and approximately 32% of the world economy in terms of purchasing power parity. Russia’s trade with this group represented 20% of its total trade in 2021, up from 12% in 2010.

From Russia’s perspective – and with other countries expressed their interest in joining the BRICS group including Argentina, Egypt, Iran, Turkey and more recently Saudi Arabia – there is much to gain from strengthening trade and economic ties and plenty of pressure to do so.

The war in Ukraine and sanctions have undermined Russia’s growth prospects. We forecast that Russia’s economy will be around 8% smaller at end-2023 compared with where it was in 2021 whereas at the end of 2021, we projected that Russia’s economy would grow by around 5% over 2022-23. In other words, Russia’s economy would have been around 14% larger in 2023 were it not for the war, indicating quite how large the economic cost has been so far.

It is unlikely that Russia fully compensates for the lost technology, export markets, and access to global financial systems through greater integration with BRICS+ partners.

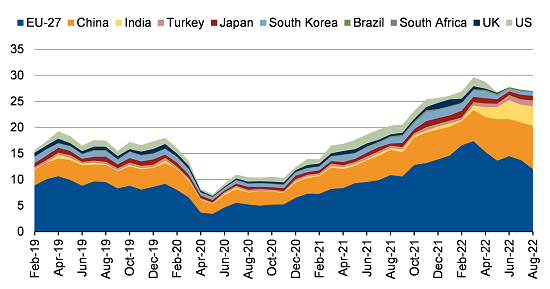

Figure 1. Russia's imports* (USD bn) show clear post-war shift to China

Source: Bruegel, national statistical offices, Scope Ratings.

*These 36 countries accounted for around 75% of Russia’s exports and imports in 2021.

Sanctions reduce Russia’s access to foreign technology

Not all the BRICS+ countries share Russia’s urgency in diversifying trade away from the United States and Europe or integrating each other’s financial systems and de-dollarising their economies, not least when increasing trading ties with Russia runs the risk of secondary US and European sanctions.

In Russia, two thirds of value added in machinery, electrical equipment and computers was typically sourced from foreign countries, with around half from the EU, US, UK, Japan and South Korea, all of which have imposed sanctions. Russia’s imports of high-tech goods and related components from these countries declined by an estimated 75% between February and August 2022. In total, goods’ imports more than halved to USD 5bn in the same period. Imports from BRICS countries jumped by almost 50% to USD 8.6bn, mainly due to trade with China (Figure 1).

It will be challenging for Russia to replace such volume and variety of sanctioned high-tech goods and other strategic imports from China or other BRICS+, find local alternatives. The US has cut off the Russian economy not only from American technology but also from foreign-produced items based on or containing it.

Russia’s use of more costly and poorer quality imported components will constrain productivity growth, crucially in the oil and gas industry, as the country develops more complex alternative supply networks. For example, the share of defective semiconductor chips imported from China has reportedly increased to 40% from 2% in the period before the escalation of the war in Ukraine.

Russia has partially diversified its energy exports away from Europe (Figure 2). Crude exports to China, India and Turkey have more than doubled since February to over 2m bpd. The three countries bought more than half of Russian exports in August and September.

Figure 2. Destination of Russia's mineral fuels exports* among 36 countries, USD bn

Source: Bruegel, national statistical offices, Scope Ratings.

*There are significant variations when comparing values with weights of Russian fuel exports since the Covid-19 crisis. This implies that changes in revenues from fuel exports reflect to a large degree changes in energy prices.

Sanctions drawbacks include oil price discounts, yuan dependence

Russia’s trade and financial integration with other BRICS+ countries will continue to increase, but not necessarily or wholly to Russia’s advantage, even excluding significant infrastructure and logistical bottlenecks that Russia faces.

Russia is finding that even in the energy trade it does not necessarily have the upper hand. Russia has had to sell crude at a sizeable discount to Asian buyers as G7 countries work towards a price cap on Russian oil sales. Russian crude trades around USD 20 below Brent ahead of the 5 December start date when EU sanctions banning import of Russian seaborne crude come into full force.

Russia’s de-dollarisation strategy will inevitably result in greater use of the renminbi which has its own drawbacks. Russia will become dependent on China’s economic policies and much larger economy, equivalent to almost 60% of BRICS aggregate output.

The Chinese yuan is increasingly perceived as a proxy for the dollar in Russia even though it lacks the international fungibility of the US currency. The yuan now accounts for around 26% of trading in the Russian foreign-exchange market, up from less than 1% before February.